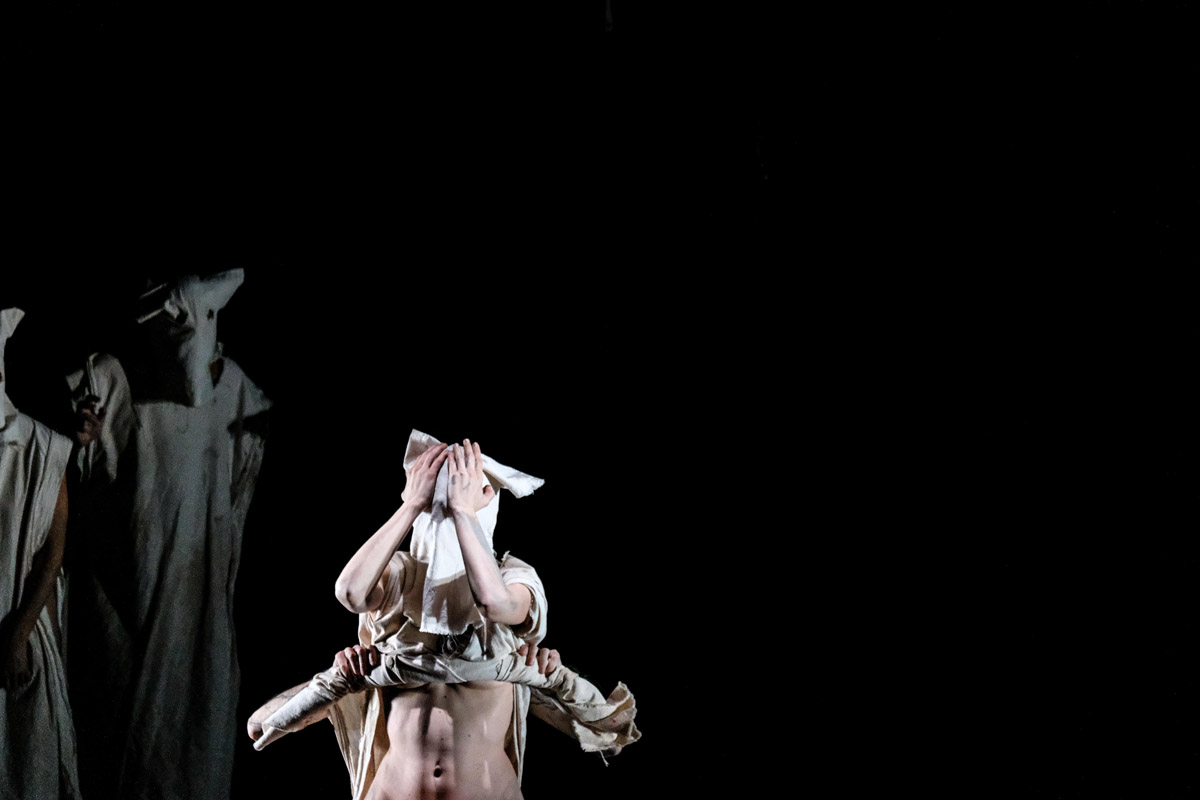

I met Margherita Pevere and Marco Donnarumma a few hours after their debut with Humane Methods at the Romaeuropa Festival as part of the Digitalive19. I’ve been aware of their work for a year, ever since I saw Eingeweide at Romaeuropa. Initially I didn’t like the show. It was strange, a bit cold but also definitely carnal, aggressive in the staging and yet extremely delicate in the choreography, immediate certainly and yet always a bit mysterious. In short, I wasn’t enthusiastic about it, but in the days and months that followed it would keep popping back into my mind in the most unexpected moments, on the subway, in the middle of a discussion with acquaintances, or while reading a novel. In those moments the images created by the duo of artists materialised in my head, disrupting my thoughts. It is from this initial feeling of annoyance and surprise of remembering that I really started to follow and study their work. I am convinced that if something I did not like immediately remains under my skin and returns incessantly as if to want to show itself again, it means that it is I who must review my judgement, that I must reassess what I felt to feed on that memory, that feeling. So this is what I did for Eingeweide, and in the literary present I find myself in the company of Pevere and Donnarumma starting a chat that I had very much sought out, and trying to explain how my being disturbed by their previous work has subsequently greatly pleased me.

Angelo di Bello: Is Humane Methods a natural evolution of Eingeweide?

P – Yes and no.

D – At the beginning it was more like taking a different road at a crossroads for us, rather than going straight on. The main idea for the project was born from a condition of unease that we as artists felt about what was and is happening in the world: intolerance, the climate crisis that no one seems to tackle, the wave of extreme right-wing politics, systemic racism and so on. So we asked ourselves: are we doing enough as artists? So in that sense, it was a bit of a drag. From a procedural point of view—the development of Humane Methods, all the research we’ve done, the discussions we’ve had with our extended team, because so many of us have worked on it—let’s say we’ve also followed an evolution of an aesthetic of a certain thought behind Eigeweide.

Margherita, you’re actually a visual artist, while Marco is more of a musician. How did this meeting happen? Not on a personal level, I know that you are a couple in real life but, on stage, what was the moment when you said to yourselves: here we are now really talking about research, as a job?

P – Deciding to work together as a couple is never an immediate or easy choice. In fact, Marco and I have known each other for several years, our conversations over coffee or the last glass of wine in the evening are always inspired by, or at least relate to art, and to research, but before deciding to work together we gave ourselves time to learn to know each other. Although we come from two different directions, a musical one for Marco and for me the visual aspect, there are some fundamental interests that converge: one of these is a critical approach, a certain kind of aesthetic and an interest in the performativity of the materials we are using. For example, Marco speaks very clearly about the body and about sound, what sound does, under certain conditions, to the body of the visitor. My work investigates, for example, how a culture of epithelial tissue cells behaves, how they transform, how to then show this to the public…

D – I agree very much with Margherita; and also, another thing that I find interesting is that we are both extremely passionate about nature and we also try to be enormously respectful of this magnificence of nature of which we are part. While Margherita has always kept it rather at the centre of her work, in very different but constant ways, for one reason or another nature has never really figured so much in my practice, and therefore working with Margherita has also been an opportunity to integrate this discourse: how to talk about nature at an artistic level…

P – …as we talk about it today. We have left behind the romanticism, we have left behind the myth of the progress of the twentieth century…

I am convinced, as an artist and as a user, that technology is still a means, a tool. It is inevitable to mention Mcluhan and his “medium is the message”, but this is never an end. In your research, also in this Humane Methods project, what is the instrumental scope of the message of technology?

D – I hope that performance art in particular will become more attentive to technology, not so much to technology as innovation but as a necessity. This is a critical necessity, because digital technology is not a novelty of the last 10 years; everything has been digital for a long time. Society does not understand this; those who understand it are simply those who govern the capitalist system in which we live, because they can make much more money with much fewer resources. Fortunately, there are wonderful works in the performing arts that use technology, but in general it is treated as a medium without critical reasoning about the medium itself. Digital technology is not a medium like a brush is for a painter: a brush is not able to change society: an algorithm is. Then there is also another aspect, and Raffaello Sanzio Socìetas gives us an idea: in the Tragedy Endogonidy there is a character impersonated by a machine, that shoots arrows. This is such a strong symbolic representation of technology, of the impact of technology, of the harshness of technology, of the violence of technology… and it is simply an automatic machine that shoots arrows at a wall. In Germany, for example, there are other theatre makers who work in this way. There is Kay Voges, the director of the Schauspiel in Dorthmund, who for several years has been working with very original and very critical theatre and technology, and whom I always recommend. But you can count them on one hand, whereas this way of working should be the standard, we should be bored of seeing so much of it.

Simone Weill said that the twentieth century man’s dream is to look like a machine, and become a machine, not so much as a prosthesis, but the worst part of looking like the machine, in being told how to think, accept an algorithm written by someone else. This is the serious problem of our society, and of how machines are used by society. I find a certain affinity with the criticism that you make of technology, and in light of this I’d like to ask you how you use technology and how you relate it to nature?

P – Personally, in my work I don’t use algorithms but, for example, I use biotechnology. It’s a little different, but it asks similar questions. To give a trivial example, we are scrupulous about accepting genetically modified foods because we consider them to be unnatural. But most people use medicines for more or less complex treatments: these also divert them from what would be a “natural state” – if ever a natural state existed. We’re all cyborgs, even without a mechanical system. We are all cyborgs when we take painkillers or other medicines, and we are cyborgs when our relationships are mediated by this (indicating my smartphone that is recording the conversation, ed). When Marco and I met we lived in two different cities and although we were very critical of technology we used phones and chat services to communicate….

D – What you were saying earlier made me reflect on how, both culturally and socially, technology is always a bit like Prometheus’ fire, something that is not ours, that comes from heaven, and as it is not ours it becomes the means of salvation, it becomes the means of control. Actually, all these things are wrong because we make the technology. We are talking about a certain type of technology, the machine, the digital aspect, etc., and that is ours, exclusively ours and being ours it is also natural because we are part of nature. It’s all part of nature, but then what are the implications? It is we who make the technology, so we should also ask ourselves questions about how we develop it and especially about how we use it, and here I feel an affinity with your idea, that is to accept certain algorithms made by certain people—it would be better to say by certain corporations, that work with a certain type of people in a certain type of context—these algorithms are accepted in our lives simply because they make things more comfortable. Comfort: this is something that we have never lost, this need for comfort. We do not realise how technology has completely changed the way we live, especially in Western societies. We speak of technology as people who have the privilege of being able to express it in the way we can in Western or Eastern societies or civilisations or in any case civilisations and societies dominated by advanced capitalism. Because then other societies that do not rely on the capitalist logic of the market, or indigenous societies, experience technology in a very different way…

P – …and you can’t generalise because we don’t know this way of experiencing technology…

D – That’s right! I admit that when I started 10/12 years ago I didn’t have this critical aspect of technology, it grew slowly, also thanks to or because of the experiences I’ve had. I’ve been working for a long time in the academic community of new musical instruments and there are fantastic technologies, but the first thing I’ve come up against is this rubber wall, so this technology that you use isn’t of much interest, these musical instruments, where they come from, who makes them and why they make them.

I find your argument very consistent with the fact that in your performances there is so much presence of the body. I think that using a body, putting it into action, able to act, the body is always a political statement. How important is it for you to have a political conscience to translate into your performances, perhaps through the body that becomes action, that is to say, to do and act?

P – It is very much so! Humane Methods is born, for example, from a reflection on what we see happening around us. The choice to put the body in the works of art has a precise basic question that is a political question. The kind of approach that we also have in our individual work has clear political reflections even if it is obviously not, as I imagine you also intend, a declaration of belonging to a political party or ideology. There are questions about why things are happening and the consequences, these are questions about responsibility and this has many ramifications. As artists both Marco and I come from a family background where there is not necessarily an artistic tradition, and so we had to, like many other colleagues, to make precise choices about how to do things, where to go, what kind of message to convey, and these are not choices dictated by luxury and opulence. Surely it’s a privilege to be able to choose to be an artist but it’s you who makes the choices and you have to answer the questions that you have to ask yourself: do you go here or there? And why? And what are the consequences? All this is found in work, with a value that is political towards society, political towards the environment in which we live. So, politics? Yes! Sure.

D – Every year that passes I notice how my work is becoming more and more radical, and this is political in several ways. It’s both bringing the body on stage and treating the body in a certain way—I like to introduce myself by saying that use and abuse bodies—but a working methodology, how you work, this is also political. For example, I don’t have a Marco Donnarumma company and this is precisely to define a statement. I have an artistic group with Margherita, with Andrea Familari, with Ana Rajcevic, with Christian Schmidts, with a lot of different people, and we work in a collaborative way; whoever does something, lifts a finger, has their name in the credits, also this is political even if obviously on a different level. And then also the idea of mixing, bastardising the disciplines that for me is also political, it’s another statement. It’s also about taking risks and not falling into the trivialisation of the themes: if you speculate on a manifestly political problem then you become the national hero and go to all the newspapers, but in reality you’re not doing anything, what you’re doing is simply supporting the common sense. This is something we try to avoid in our work. That’s why in our work we try to talk about these things in many different ways.

The last question is about the public: what relationship are you in and what kind of relationship do you seek with the public?

P – The public also depends very much on the context in the work is shown. A work such as Eigeweide can go to the Muenchner Kammerspiele, can go to a festival, can go to a museum and we brought it to all three. Marco’s installations, my installations have an audience that depends on the context. About the relationship with the public… I really like what you described about something that enters and remains like woodworm. When I have this feeling, often they are works that then accompany me, I do not necessarily like them but they stay with me. What you have described also shows that you are disturbed at first and then it turns out to be something undecipherable. Only if there is this enigma will you think about it and keep thinking about it, and what I would like to be able to communicate to an audience is an enigma. Spectators can think, they can also find criticisms to make, but it is not a linear relationship, it is not a delivery, it is not something that makes you content or satisfies certain needs; on the contrary it is disturbing, it forces you to squirm before finding your answer.

D – I agree with what Margherita says. For me it’s important to understand how to make the audience uncomfortable to a certain extent so they don’t quite want to leave the show, but almost. I’m very interested in understanding the audience in this sense, how much you can risk, how much you can push yourself. Because if you can find that very small edge, then you can create works that really make an impact. What I hope every time I start a new work is that it has an impact, not a media impact but an impact a bit like Margherita described before, and how you described your experience with Eigeweide. This for me comes from an idea that I have always had: the critical sense must be developed by everyone, by as many people as possible, and the more years go by, the less it is developed. Instead, it is essential to develop a critical sense, so in my work I don’t want to say things, I want to prod you to develop a certain kind of critical sense, and I try to do this at the perceptual level, at the body level and a little bit at the brain level, even if then the rationalisation always takes away something, so I try to always go a little deeper, inframuscular.

This conversation took place on occasion of the performance Humane Methods by Marco Donnarumma and Margherita Pevere in Rome at the Digitalive 2019, event of the Romaeuropa Festival dedicated to algorithmic performance curated by Federica Patti. Eigeweide, evoked in the text a number of times was performed by Marco Donnarumma and Margherita Pevere for Romaeuropa Festival. Digitalive 2018.

images: (cover 1-2-3-4-6) REF19_Digitalive.04.10, Marco Donnarumma, Margherita Pevere, «Human Methods», ph: Giada Spera (5-7-8-9) REF19_Digitalive.04.10, Marco Donnarumma, Margherita Pevere, «Human Methods», Piero Tauro