The City of Milan and the Museum of the 20th century are dedicating a retrospective to visionary and versatile artist Bruno Munari (1907-1998). Starting from the analysis of his series of Macchine Inutili/Useless Machines Luca Zaffarano reconstructs a full portrait of the artist that Arshake will be publishing on a weekly basis. The Useless Machines reconnect with the many aspects of the artist, illustrated by unpublished photographs by Pierangelo Parimbelli.

The exhibition presented by the city of Milan and the Museum of the 20th Century (Museo del Novecento) is celebrating Bruno Munari, one of the great protagonists of the Italian and international art scene. Curated by Marco Sammicheli, this retrospective exhibit will be open to the public from April to September 2014 and will display many works from the Jacqueline Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation in Milan. A selection of works by this Milan native are exhibited along with those by many other artists present in the hosting museum’s collection. Works by Franco Grignani, Paolo Scheggi, Getulio Alviani and Giulio Paolini (to name a few) are similar in method and production to Munari’s experimental manner of interpreting art. Munari, as an artist, developed and matured along the track of futurist experimentations and was a prominent figure and knowledgeable reference point for many of the protagonists of the most experimental movements (Futurism, Abstract art, Concretism, Kinetic art, Programmed Art, Multiplied art). However, he always maintained his continuity of thought in evolution and lateralization while undertaking these experiments that transcended any definitive classification. In the words of the exhibition’s curator: « Munari Politecnico is the story of a versatile artist, his role in Italian and European art during the 20th century and the relationships which led to his becoming an eclectic protagonist. Munari used painting, sculpture, collage, luminous installations, works on paper and technical experiments to drive his artistic quest into a marginal land». We are interested in taking advantage of the opportunity offered by such a re-evaluation to delve into the theme of Munari’s début on Milan’s Futurist scene in the 1930s: the Useless Machines.

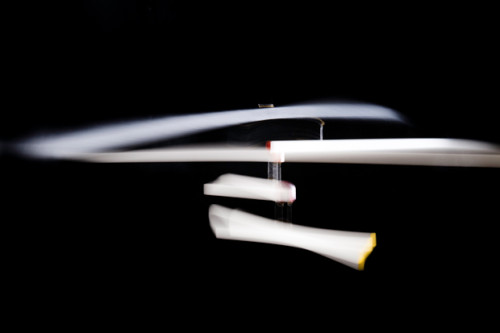

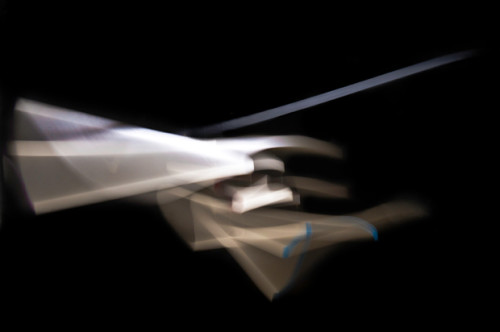

We will describe these works in detail, analyzing the many characteristics of their design (all present at the same time) which accentuate a composite thought of extraordinary complexity. We will use exclusive images – available to the public for the first time – to illustrate the poetic wealth of these works and analyze the formal properties listed below:

- Dynamism of an indefinite form

- Kinetism

- Spatiality

- Programming

- Chance

- Abstraction

- Installation

- Perceptive instability

- Creation of natural forms

- Bruno Munari and the Useless Machines

The dynamism of indefinite form.

Bruno Munari was born in Milan in 1907 but spent his childhood and teenage years with his family in Badia Polesine in Italy’s Veneto region. He returned to Milan in 1926 and started to follow the Futurist movement at the age of 19, displaying his work immediately in group expositions in Italy and Europe. For fifteen years, from the late 1920s to the early 1940s, his composite activity was delineated along the path traced by the theoretical reflections of the Futurist movement. He showed an interesting autonomy of expression which was acknowledged and encouraged by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. As many scholars agree, The Ricostruzione Futurista dell’Universo (Futuristic Reconstruction of the Universe) manifesto penned in 1915 by Balla and Depero reveals a Munari already in nuce[1], (in bud) first and foremost for his ability to create dynamic forms that are immaterial and evanescent. The theme of the dematerialization of art is a constant in Munari’s art throughout his career: «More than anything else, I believe that what needs to be taken most into consideration is the passage of a form, which has its dimensions, through a metamorphosis, as a fluid, to become another form. That way, there is no longer a definite form but a moment of passage from one form to the next and this can only be recognized through motion».[2]

The name Bruno Munari is strongly linked to the Useless Machines he began building in the early 1930s. They were first featured in collective exhibitions of the Futurist movement and the artist used such poetic titles as Sensitive Machines[3], Volumes of air or Breath of machine.[4] Practically at the same time, the artist proposed a paradoxical name for his particular idea of abstract art floating through space. A name that has the undeniable merit of making us pause and reflect through the syntheses of an oxymoron: on the uselessness of that which is useful (the machine) and usefulness of that which is useless (art).

So, Munari created machines to hang from the ceiling made up of elements of extremely light material (such as sticks of balsa wood, cardboard leaves painted on both sides, blown glass, spring steel wires) that move freely through space without any constraints amongst themselves. The Useless Machine is a composition with a dynamic transformation that tries to leave the spectator with the perception of an unstable form.

The photographs we have chosen tend to accentuate the characteristic of motion and the resulting dynamism. Every single element in the machine is able to generate virtual volumes and photography gives the impression of a sculpture that develops in space, a sculpture with many debts. There is no doubt that its biggest debt is to Umberto Boccioni’s Unique forms of the continuity of space.

Lastly, we would like to remember Useless Machines with the words Dino Buzzati used to describe them in 1948: «The fact is that these sticks have their own lives, as if they were animated by some kind of spell. They rotate slowly; they vibrate, bend and open up much like the way a peacock spreads its wings, shaking like leaves. All it takes is for someone on the other side of the room to clear their throat or the heat of a lamp or even an imperceptible breath of air that sneaks in through the window and the sticks start to tremble. In other words, since no environment can ever be absolutely still – not even behind closed doors – these sticks are in perpetual motion»[5].

[1] Aldo Tanchis, Bruno Munari, Idea Books Edizioni, Milan, 1986, page 11.

[2] Dialogo con Bruno Munari by Miroslava Hàjek, in Miroslava Hàjek (edited by), Bruno Munari Instalace, Catalogue for his solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art Klatovy, Klenova Gallery (Czech Republic), 1997.

[3] Danilo Presotto (edited by), Quaderni di Tullio d’Alibisola, n. 2 (1928-1939), Editrice Liguria, Savona, 1981, page 141.

[4] Enrico Crispolti (edited by), Nuovi Archivi del Futurismo. Cataloghi di esposizioni, De Luca-CNR, Rome, 20120, pages 575-577

[5] Dino Buzzati, Le Macchine Inutili di Munari, in Pesci Rossi, monthly dedicated to current literary events, n. 10-11, October-November 1948, year XVII, pages 14 – 15.